There is so much misinformation about sensor sizes out there, and so much written and spoken information that is just wrong, I thought I’d do an article exploring the truth.

But firstly, a word to the wise. If you want to be able to fully understand this article, you will need to have a full understanding of depth-of-field and the effect of aperture size on that depth-of-field. So if that’s still a bit of a struggle for you, you should read some articles to develop a full understanding of that first. It will also help if you have an understanding of dynamic range in cameras.

First thing I’d like to talk about is this phrase “full-frame” sensor. The implication of that would seem to imply that other sensor sizes are only “part frame”, or perhaps somehow incomplete? We might be led to believe by this term “full-frame” that an iPhone sensor (which is very small indeed) is only a fragment of a sensor, and yet they produce trillions of images every year that people seem very happy with.

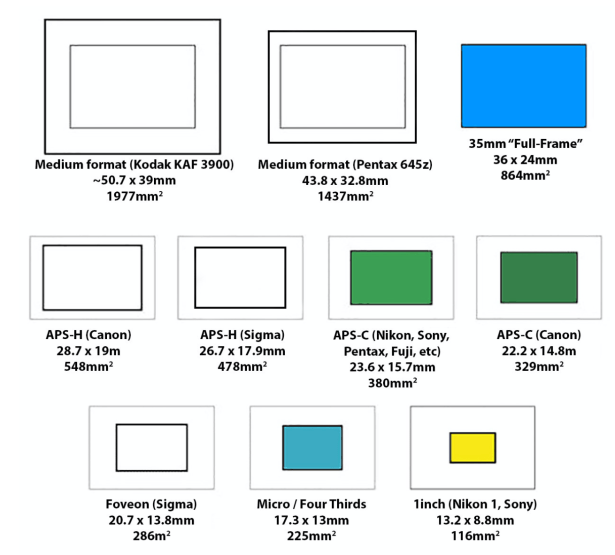

So, to get down to business, there is no such thing as a “full-frame” sensor, but the phrase does date back in photographic terms to a time when there was such a thing as a “half-frame” camera. One such was the Olympus Pen, produced in Japan in 1959, and it used 35mm film, but took twice as many shots on a roll of film as other 35mm cameras. A normal photograph taken on a 35mm film camera produces an image on the negative of 24 x 36 millimetres. The “half-frame” Olympus pen produced a vertical format shot of 18 x 24 millimetres, and on a 36 exposure roll of film, you could get 72 shots. Hence, 24 x 36 became known as “full-frame” This normal 35mm film frame size of 24 x 36 is the point under discussion. This is the size of the sensor commonly known as full-frame. But if that’s “full-frame” what is an image coming from a medium format camera, traditionally 60 x 45 millimetre, 60 x 60 millimetre or 60 x 70 millimetre? Then, even larger than that, there are plate cameras that produce an image size of 5 x 4 inches, or 8 x 10 inches on the negative, (which translates to 127 x 102 millimetres for the 5″ x 4″, or 229 x 254 millimetre for the 8″ x 10″ cameras). So the 24 x 36 millimetre cameras were nothing other than just the “most-common” size, and many serious photographers considered them far too small for really good quality photography.

Time, though, has moved on, and we now live in a digital era. The essential mechanics of photography remain precisely the same as they were 194 years ago, when it all started. Exposure, depth-of-field, ISO…all those things are just the same today and require exactly the same control today as they did back then. All that has changed is that where the film used to sit in a camera, now sits a digital sensor. The manufacture of camera sensors is an expensive process, and the cost of producing a plate film sized camera would be prohibitive (though quite wonderful). The earliest digital cameras had very small sensors because of this, but around ten years ago, it became more cost effective to fit sensors the same size as traditional 35mm film, so all the familiarity of 35mm photography came back. Once again, a 28mm lens was wide angle, and 135mm was an ideal lens for portraiture, and for those long involved in photography, such as myself, things kinda got back to normal. And as time moves on and manufacturing costs become less, medium format cameras are starting to come to market. The Fujifilm GFX100 comes to mind, with its 102 Megapixel 43.8 x 32.9 millimetre sensor. So, if the misnamed “full-frame” sensor is wonderful, this beast must be extra wonderful. And it is, in many ways. But this leads us to the point of this article, which is to discuss the practical advantages and disadvantages of the various different sensor sizes.

I myself, at least for the present, am a Canon APS-C camera user, a choice I made because it suits my photography very well, and I am extremely familiar with it, knowing exactly what result to expect from a given ISO/Aperture/Shutter Speed combination with a particular lens at a particular focus distance. These cameras have what’s known as a 1.6x crop sensor, of 23.6 x 15.6 millimetre proportions. When I take a shot with these cameras, I can have a print of 6 x 4 inches, the same size as a 24 x 36 millimetre sensor without any cropping or cutting off of any part of the image. That’s because the sides of the sensor are in the same ratio of 3:2 . 3 units along the long side, 2 along the short side. Or a six inch x four inches print, also a ratio of 3:2 .

Hmmm. So, where does the “crop” come in. Well, that really relates to the lenses. If I used a lens designed for a 24 x 36 millimetre sensor, part of the image cast by that lens would be missed, or fall off the edges of my 23.6 x 15.6 millimetre sensor. In other words, the image projected on to the sensor, by the same lens, would be cropped. But I’m not using the same lens; I’m using a lens, or lenses, designed for my camera that projects an image that fits my sensor. In order to get the same amount of subject on my smaller sensor, it will need to be a wider angle lens. Since the crop factor of my Canon APS-C cameras is 1.6, that means that for an image I take on my camera with a 10mm lens, it would need to be a 16mm lens on a 24 x 36 millimetre sensor camera (or full-frame if you’re stuck with that terminology) to get the same shot.

So moving on, there are advantages and disadvantages of different sensor sizes. Wide angle lenses, by virtue of the mathematics involved in their design), allow a greater depth-of-field than lenses of a longer focal length. And of course, lenses of a longer focal length allow shallower depth-of-field than wide angle lenses. This is the simple mathematical fact that means larger sensored cameras can allow shallower depth-of field (because they need longer focal length lenses), giving a blurred background to your subject. Of course, the medium format cameras I spoke of earlier need even longer focal length lenses causing even shallower depth-of-field. To sum that up, if you want shallow depth-of-field, a larger sensor can be an advantage. If, on the other hand, you really need more depth-of-field, as you often do with landscape photography or video, then a larger sensor can be a disadvantage.

This information about the effect of sensor-size on depth-of-field, the advantage or disadvantage it presents you, is not the end of the world. Depth-of-field can be manipulated by other means. The focal length of the lens and the aperture set on that lens also directly control depth-of-field, so you can change these parameters to achieve the effect you require, and that fact, at least in part, dispels that particular advantage/disadvantage.

Now we arrive at another, more pertinent point about sensor sizes. What really matters, is pixel density. To put this simply, larger pixels, more accurately called “photosites”, are better at gathering light and colour information. So for any sensor size, a smaller number of pixels means the pixels can be larger and therefore better at collecting light. However, the more pixels you have on a sensor, the better it’s resolution will be, resulting in larger file sizes which enables larger images, especially important for printing large images. So you can now see that a balance needs to be struck; a 1 megapixel sensor, like that in my first digital camera, can only produce small prints, and generally not very good images. Fifty or sixty megapixels on a 24 x 36 millimetre sensor will be very small pixels indeed, and not so good at capturing the light information. So in theory, you could produce huge prints, but the image might feature poor colour and contrast, which will need to be greatly processed by the camera’s processor to produce an acceptable result. This is the same, essentially, as applying too much processing to a shot in Lightroom or photoshop etc., which result in an impaired image.

The implication of this need for reasonably large pixels, and a reasonable number of them, leads to the assertion that large sensors are therefore better, in this respect. It’s always a matter of “horses for courses” though. Sony produce various versions of their excellent Alpha 7 cameras at the time of writing; the A7s mark 2 (12 megapixels), the A7 mark 3 (24.2 megapixels), and the A7R mark 4 (a whopping 61 megapixels). The A7s Mark 2, is primarily aimed at the video market, but it also produces quite stunning low light images. It’s very large pixels are extremely good at catching light, and this camera can actually see things in the dark that the human eye can’t, so it is quite astounding at low light video. As you get through the range up to the A7r (mk3), this ability to produce excellent images in low light diminishes. At the same time the resolution (or file size) gets significantly larger, so you can print larger images. So the decision, when you’re making your choice of cameras, becomes complicated; do I need excellent low light performance versus potentially large print sizes. In theory, if you need a 300 pixel per inch print, the largest size print you can get from a 12 Megapixel camera will be a little less than 15 x 10 inches. In reality though, a larger print is usually viewed from further away (think advertising billboard), so you can reduce the printing resolution and print larger. I have 20 x 30 inch printed images from an 8 Megapixel camera that are very acceptable at a normal viewing distance.

For the purpose of comparing pixel density between cameras/sensors, we can calculate the number of pixels per square centimetre for any particular sensor, and thus get an accurate comparison. To take a couple of examples, the Sony A7R mark 4 has a sensor size of 24 x 36 millimetres, a total of 8.64 cm2. Dividing the number of pixels (61 million) by this, gives us (61,000,000/8.64) 7.060 million pixels per cm2 . Let’s compare this to a Canon EOS 7D mark 2, with its 23.6 x 15.6 millimetre APS-C sensor, at 20.2 megapixels (20,200,000/3.682), gives us 5.486 million pixels per cm2. Obviously the individual pixels are larger in the Canon, and all things being equal, should be better at capturing light. All things, however, are not equal, and with the Sony camera being three years newer than the Canon, it’s reasonable to expect that the sensor and processing technology will have evolved in that time, but theoretically, the cameras would not be that far apart in terms of dynamic range. And that’s the other very important factor determined by pixel (or photosite) size. That ability of larger pixels to better capture light means that they can also see detail in the darker areas of an image better and thus allow the camera to have a greater dynamic range. Dynamic range is the difference between the lightest and darkest areas in a scene that the camera can capture. The bigger that range is the better, as that determines how much detail can be shown in dark or light areas before they become “blown-out”, which means to record as pure black or pure white. In fact, the Sony A7R mk 4 claims to have a dynamic range of 15 stops, compared to the Canon EOS 7D mk 2 which claims only 11.8 stops. That’s a substantial difference, so the technology is moving on, and fast.

It must be becoming obvious that it’s not a clear choice to decide you must have a larger sensor. If you are, for example, a wedding photographer who presents photo albums to your clients with images 15 x 10 inches in size, then a 12 megapixel camera will be quite adequate. And 12 Megapixels, even on an APS-C sensor, is really good quality and gives you a lot of advantages with the right lenses. On the other hand, if you’re an advertising photographer who shoots billboards, you are going to want images as high resolution as possible, and I’d point you in the direction of a medium format camera like the fujifilm GFX 100. Your budget for camera and lenses will need to be fairly healthy though…think $20,000 AUD, and more if you want a whole bank of different lenses).

The photography that I personally do is sometimes printed, but not really too frequently, it’s more often viewed on screen. I do, however, always shoot with printing in mind though, so I always use the highest quality settings possible. I do a lot of stitched panoramas using longer lenses, often needing good depth-of field. I rarely do low light work. I also combine images to achieve very high dynamic range of 20 stops or more. Any people photography I do, I use longer focal lengths and wider apertures to give me shallower depth-of-field. I occasionally shoot video with my Canons so wider depth-of-field is an advantage. Most video I do is with an even smaller sensored camera, for even deeper depth-of-field. Taking these things into account, I arrived at the conclusion that my Canon Pro-level APS-C censored cameras, at 20Mp, fit the bill for me, and I have a full range of lenses, so changing systems would be a major decision. What I’m really saying here, is that with the technology available in post-processing, the skills to use it, and good quality lenses, my current equipment is very much up to the game. I can’t see any reason to change at the present time, but if I did, it would possibly be to medium format, particularly as it becomes more affordable, and the range of lenses improves.

I do hope this information shines some light into the darkness. Give me a shout in the comments if you have any questions.

Jim